In Depth

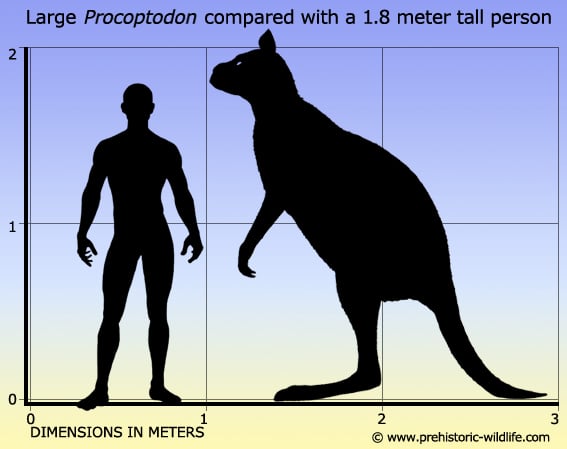

During the Pleistocene Australia had a variety of animals that loosely resembled those still living today but on a much grander scale, from giant three meter long wombats like Diprotodon to four meter plus goannas like Varanus priscus. Procoptodon for its part was essentially a giant kangaroo, although its full size has been the subject of mis-interpretation by some authors. Procoptodon itself stood no more than two metres high, but it could use its long arms to reach up to three meters high, a figure that has in the past been erroneously presented as the full height of the animal.

Procoptodon seems to have been one of the more abundant members of the Australian Pleistocene megafauna and seems to have been active in different habitats wherever there was ample growth of plants to support the population. These areas included the growth of tall plants, shrubs and trees that would have been out of reach for many of the animals of the time, and this is where the large size of Procoptodon comes in. First by being tall, the shoulders are higher up off the ground, which immediately gives Procoptodon a reach advantage over smaller kangaroos. The long arms also had hands that had two enlarged fingers tipped with curved claws which could quite conceivably have been used to wrap around tall branches and pull them down to the mouth, much like how the giant ground sloths of the Americas lived during this time. Procoptodon also had forward facing eyes which would have granted it the all-important depth perception that would have been required so that it knew exactly how far it had to reach in order to pull down the next branch.

How Procoptodon ate can also be revealed in the shape and proportions of the skull. Shorter faced animals usually have the adaptation of a shorter snout so that they can more easily process food with the rear teeth. This is a simple principal where the point of jaw articulation is actually the fulcrum of the mechanism that allows an animal to open and close its mouth and allows the jaw closing muscles to focus more force upon shearing through food. In Procoptodon this food could have been parts of sclerophyll plants that were soft and nutritious within, but had a tough exterior to protect the inner parts from drying in the harsh Australian climate. The dentary (lower jaw) was fused and well developed so that it could easily withstand the stresses of the more powerful jaw action. The teeth were also well adapted for this with low crowns that exhibited extra folds to increase their food processing potential. Despite its large size, Procoptodon would have been prey to the larger predators of the time such as Thylacoleo, better known as the marsupial lion, that is often envisaged as dropping down from trees to hit is prey from above. Also was the aforementioned Varanus priscus, a huge monitor lizard that could have lain in denser areas of vegetation to surprise any unsuspecting Procoptodon that ventured too close. Procoptodon was not completely defenceless however, although its best defence against predators would have been speed. Most of the metatarsals of the foot were reduced with the exception of the fourth digit that had become so enlarged that in life Procoptodon would have been seen to have but a single toe. This single toe was actually stronger and would have been less susceptible to injury that several toes that would have meant more but smaller and weaker bones. The leg bones were also proportionately more robust than those of smaller kangaroos with the larger surface areas providing enlarged anchor points of tendons that attached to the proportionately more powerful leg muscles that would have been necessary to propel the larger and heavier body. Used correctly these legs would have also been a considerable weapon against predators, as well as rival Procoptodon since kangaroos can be observed today balancing on their tails while kicking out at an opponent or something they perceive as a threat.

The disappearance of Procoptodon from Australia seems to coincide with the arrival of the first humans on the continent, although the precise date remains a matter of debate with some sources claiming that Procoptodon may have survived to as recently as just under twenty thousand years ago, while others remain steadfast to the disappearance occurring forty to fifty thousand years ago. The cause of their extinction is also debated, but the main theory is effects of people that comes in two parts. The first is that Procoptodon may have been hunted by early humans for food, although it seems unlikely that people would or even could have hunted one of the most common large marsupials of the time into extinction. A contributing effect is that of fire stick farming where vast expanses of land are set alight to encourage fresh growth of plants that are more easily consumed than the existing growths already there. This would cause a shift in the availability of plant types that may have suited other herbivorous animals better than Procoptodon, leading to increased strain upon the species.

Further Reading

– Systematics and Evolution of the Sthenurine Kangaroos – University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 146: 1–642 – Gavin Prideaux – 2004. – Ecological and evolutionary significance of sizes of giant extinct kangaroos – Australian Journal of Zoology 54 (4) – K. M. Helgen, R. T. Wells, B. P. Kear, W. R. Gerdtz & T. F. Flannery – 2006. – Extinction implications of a chenopod browse diet for a giant Pleistocene kangaroo – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106.28 (2009) – Gavin J. Prideaux, Linda K. Ayliffe, Larisa R. G. DeSantis, BlaineW. Schubert, Peter F. Murray, Michael K. Gagan & Thure E. Cerling – 2009.