In Depth

Megantereon has a popular standing within the realm of big cat palaeontology as it is thought by many to be the ancestor to the considerably more famous Smilodon (often incorrectly dubbed the Sabre-toothed tiger). Megantereon itself is often referred to as a dirk toothed cat because while the upper canines are enlarged, they are still smaller and more gracile than the teeth of the later Smilodon. The lower jaw however still has special flanges to house the upper canines when the mouth was closed, and these teeth are thought to have been the primary tools for killing prey.

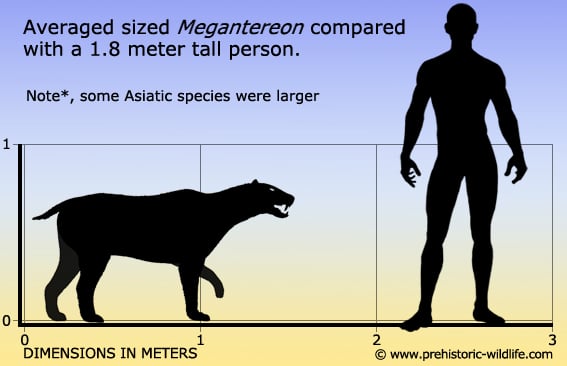

Examining the post cranial skeleton of Megantereon has revealed that the living animal was fairly robust, especially around the fore quarters. This means that Megantereon was not built for speed and almost certainly did not spend its time sprinting after prey across open ground such as other big cats like Miracinonyx (often called the ‘American cheetah’). Instead Megantereon’s hunting behaviour was most probably that of an ambush hunter that waited for prey to get close before pouncing. Megantereon’s size makes it possible to have climbed into trees, something that may have been quite easy for it to do considering the well-developed forelimbs. If Megantereon took up position above a path used by travelling herbivores (say to and from a water source) it would only be a matter of time before potential prey passed along the path. Megantereon could then drop down from the tree to surprise its prey from above. The enlarged canines of Megantereon like other similar big cats are actually comparatively weak compared to the smaller teeth. This is because their larger size means that they act like bigger levers which can magnify sideward forces against the tooth which leads to an easier tooth break. This is something that a specially adapted predator like Megantereon could not afford to happen as without the specialisation it would lose its edge to stay alive. This is why old ideas of Megantereon biting into prey and holding on with its mouth as it was thrown around while the prey struggled are no longer considered likely, the teeth were simply not capable of withstanding those kind of stresses.

A more likely scenario is that Megantereon would use its enlarged canines to inflict a single devastating bite and then back off while the prey died. Some however point out that the main problem with this kind of strategy is that the prey would take time to die and would attract other predators while in its death throes. But how fast an animal dies from a bite does not depend so much on how it is bitten but where it is bitten. When ambushing prey Megantereon probably would not just lunge and bite the first body part it could, instead it would probably focus on a key weak area like the neck. Not only does the neck contain the windpipe, but also important arteries that carry blood direct from the heart to the head and brain. If Megantereon could sever an artery like this, something that its large canines would have easily been capable of, then death for the prey animal would at most be just a few minutes. The well-developed fore limbs of Megantereon may have also allowed it to steady prey as it bit into the neck, further reducing the risk of dental injury. Unless another predator had seen the attack as it happened, Megantereon would be able to at least get a few mouthfuls of flesh before it was disturbed, and if adept at climbing and assuming the prey was not too large, it may have been able to drag its kill into a tree and buy itself more time to feed before being disturbed by other predators (Such behaviour can be seen in Leopards today).

Megantereon has for a long time been thought to have a New World origin because the oldest fossils came from North America and were dated at being around four and a half million years old. Other fossils from Europe (specifically France) are dated at no more than two and a half million years ago, while most of the African remains only reached up to three and half million years ago. This thinking was unchallenged until the discovery of new but very fragmentary material from Africa (Chad and Kenya) that has been dated to between just over five and a half and seven million years ago. If this identification and dating is correct then Megantereon may have originated in central Africa, radiating out towards Europe and Asia before crossing the bearing land bridge into North America.

When Megantereon disappeared is so far a little easier to determine. In North America Megantereon is thought to have evolved into the first and smallest species of Smilodon, S. gracilis, approximately two and half million years ago. In Europe no remains are known to be younger than nine hundred thousand years ago, and Megantereon seems to have begun to disappear from Africa one and half million years ago until seven to four hundred thousand years ago where the youngest remains are known from southern Africa. Asian populations may have been more stable with remains in China dated to five hundred thousand years ago.

Megantereon has a long history that dates back to the early days of palaeontology in the first half of the nineteenth century. Because of this numerous sets of remains have been attributed to the genus under a large number of species names. Modern analysis of these remains however suggests that all of the different species that have been recorded for so long may actually represent a much smaller number of valid species. Most palaeontologists recognise M. cultridens, M. falconeri and M. whitei, as being valid, but which of the remaining number remains valid depends more upon the interpretation of those examining them. What does not help this matter is that with the exception of one quite well preserved specimen from France, most of the other sets of remains are very incomplete and of a fragmentary nature.

Further Reading

– Megantereon hesperus from the late Hemphillian of Florida with remarks on the phylogenetic relationships of machairodonts (Mammalia, Felidae, Machairodontinae). – Journal of Paleontology 57(5):892-899 – A. Berta & H. Galiano – 1983. – On the presence of Megantereon whitei at the South Turkwel Hominid Site, northern Kenya. – Journal of Paleontology – J PALEONTOL 01/2002; 76(5). – Paul Palmqvist – 2002. – Species Identification in Megantereon: A Reply to Palmqvist – Journal of Paleontology 76(5):931-933. – Lars Werdelin & Margaret E. Lewis – 2002. – Megantereon fossil remains from Renzidong Cave, Fanchang County, Anhui Province. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 43(2):122-134. – J.-Y. Liu – 2005. – A Re-Evaluation of the Diversity of “Megantereon” (Mammalia, Carnivora, Machairodontinae) and the Problem of Species Identification in Extinct Carnivores. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology – Vol. 27, No. 1 (Mar. 12, 2007), pp. 160-175 – Paul Palmqvist, Vanessa Torregrosa, Juan A. P�rez-Claros , Bienvenido Mart�nez-Navarro & Alan Turner – 2007. – Osteology and ecology of Megantereon cultridens SE311 (Mammalia; Felidae; Machairodontinae), a sabrecat from the Late Pliocene – Early Pleistocene of Sen�ze, France – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society vol 151, issue 4, p833-884. – Per Christiansen & Jan S. Adolfssen – 2007. – The African species Megantereon whitei from the Early Pleistocene of Monte Argentario (South Tuscany, Central Italy) [L’esp�ce africaine Megantereon whitei du Pl�istoc�ne inf�rieur du Mont Argentario (Sud de la Toscane, Italie centrale)] – Comptes Rendus Palevol vol7 issue 8, p601-606. – Raffaele Sardella, Mauro Petrucci & Lorenzo Rook – 2008. – New sabre-toothed cats in the Late Miocene of Toros Menalla (Chad). – Systematic palaeontology (Vertebrate palaeontology) Comptes Rendus Palevol 9, 221-227. – L. De Bonis, S. Peigne, H. T. Mackaye, A. Likius, P. Vignaud & M. Brunet – 2010. – First discovery of Megantereon skull from southern China. – Historical Biology. 0: 1–10. – Min Zhu, Qigao Jiangzuo, Dagong Qin, Changzhu Jin, Chengkai Sun, Yuan Wang, Yaling Yan & Jinyi Liu – 2020.