In Depth

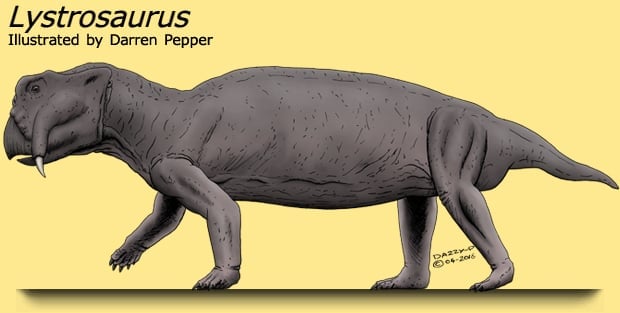

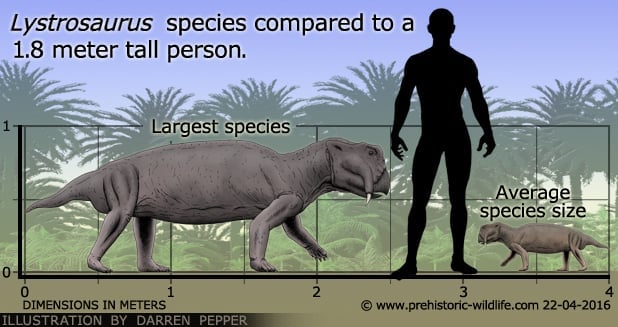

Lacking teeth in the usual sense, Lystrosaurus had two tusks, typical of the dicynodonts. These tusks projected downwards from the maxilla, and are thought to have been used to dig up the nutritious roots of plants that grew in the arid climates of the time. It is also thought that Lystrosaurus had a horny beak for snipping off vegetation above ground which would then be ground against a horny second palate in its mouth. Study of the lower jaw shows that it was adapted to move back and forth to aid in this grinding process. The stout body of Lystrosaurus was supported by four legs that were in a semi sprawling position. This means that while Lystrosaurus carried itself up off the ground, the legs would stick out to the sides as opposed to supporting its weight underneath like columns.

Lystrosaurus was exceptionally common in the early Triassic, and may have formed as much of ninety-five per cent of the total known vertebrate population. It is thought that the aftermath of the Permian extinction involved a lack of both competitive herbivorous animals and large predators capable of taking down a fully grown Lystrosaurus caused this, the result of which was Lystrosaurus becoming the dominant land vertebrate of the time.

During the course of its discovery many more species have been attributed to the Lystrosaurus genus, but they are not recognised by all. The huge amount of fossil material that exists for Lystrosaurus means that the total accepted species can and are likely to fluctuate over coming years.

Further Reading

– Contributions to the knowledge of the reptiles of the Karroo Formation. 3. The skull and other remains of Lystrosaurus putterilli, n. sp. – Annals of the Transvaal Museum 5:214-216. – E. C. N. Van Hoepen – 1915. – Preliminary description of some new lystrosauri. – Annals of the Transvaal Museum 5:214-216 – E. C. N. Van Hoepen – 1916. – On two skeletons of Dicynodontia from Sinkiang. – Bulletin of the Geological Survey of China 14:483-517 – C. C. Young – 1935. – On some new genera and species of fossil reptiles from the Karroo Beds of Graaff-Reinet. Annals of the Transvaal Museum 20:157-192 – R. Broom – 1940. – On the genus Lystrosaurus Cope. – Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 33(1):107-120 – A. S. Brink – 1951. – Lystrosaurus primitivus, sp. nov. and the origin of the genus Lystrosaurus. – Annals and Magazine of Natural History 7:407-426 – M. J. Toerien – 1954. – [Preliminary report of a new species of Lystrosaurus of Sinkiang]. – Vertebrata PalAsiatica 8(2):216-217 – A. L. Sun – 1964. – The first Lystrosaurus find from the territory of the European part of the USSR. – Palaeontologicheskiy Zhurnal 4:140-142 – N. N. Kalandadze – 1975. – Lystrosaurus georgi, a dicynodont from the Lower Triassic of Russia. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (2): 402–413. – M. V. Surkov, N. N. Kalandadze, M. J. Benton – 2005. – Lystrosaurus species composition across the Permo–Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. – Lethaia 40 (2): 125–137. – J. Botha & R. M. H. Smith – 2005. – Cranial variability, ontogeny and taxonomy of Lystrosaurus from the Karoo Basin of South Africa. – Amniote paleobiology. Perspectives on the Evolution of Mammals, Birds, and Reptiles,. University of Chicago Press. pp. 432–503. – F. E. Grine, C. A. Forster, M. A. Cluver & J. A. Georgi – 2006. – Evidence of torpor in the tusks of Lystrosaurus from the Early Triassic of Antarctica. – Communications Biology. 3 (1): 471. – Megan R. Whitney & Christian A. Sidor – 2020.