In Depth

Herrerasaurus was first described in 1963 yet many sources still cite the year 1988 as the year the genus was discovered. In actually however this was the year that the first complete skull of Herrerasaurus was found, and because this is the discovery that really made headlines in the scientific press, this is the date that some who don’t bother to do more complete research put forward as discovery of the genus.

The actual phylogenetic placement as well as wider implications of Herrerasaurus has been the subject of a lot of debate amongst palaeontologists. With its bipedal stance and skull features Herrerasaurus is considered by some to be a basal theropod (the line that would go on to produce giants like Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus), while other palaeontologists think that Herrerasaurus is a basal saurischian (lizard hipped) dinosaur that is similar and related to the theropods, but is still separate from them. Some palaeontologists also think that Herrerasaurus is an even more primitive dinosaur that predates the first major split into saurischian and ornithscian (bird hipped) groups of dinosaurs.

Clear identification is not helped by the fact that Herrerasaurus has a number of features that are spread out across all groups of dinosaurs, although the individual features are not found in each group. As always the placement of a prehistoric animal depends upon the interpretation of the researchers in question, but the main problem is that the early dinosaurs of the Triassic are not as well-known as the later Jurassic and Cretaceous dinosaurs, and are often known from even more partial and incomplete remains. As time goes on however it is inevitable that more fossils of Triassic dinosaurs will be found, and with luck they will allow for a much more complete picture of dinosaur evolution.

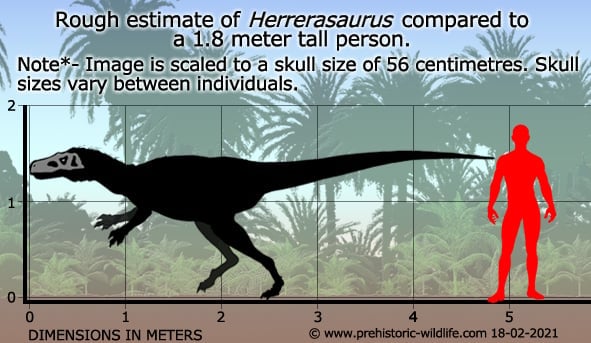

As a dinosaur Herrerasaurus was actually one of the larger dinosaurs currently known with most other forms such as Eoraptor being towards the one meter length mark. Despite its size over other primitive dinosaurs Herrerasaurus was probably not the top predator of its ecosystem as the large rauisuchian Suchosaurus was also active in the same area.

The basic theropod skull form can already be seen in Herrerasaurus along with a similar dental arrangement. As a predator Herrerasaurus probably focused its hunting upon small reptiles as well as the smaller dinosaurs. The long legs of Herrerasaurus would have seen it easily able to keep pace with the smaller dinosaurs, and it was probably one of the few predators that were able to catch them. Larger reptiles like the rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon were more heavily built and may have also been attacked, although its stocky build may have meant that smaller juveniles were more likely to be taken.

A skull feature of Herrerasaurus that is usually not seen in other dinosaurs is that of a sliding lower jaw. This sliding jaw can be seen in some other reptiles though so this feature is more probably a case of individual specialisation rather than an evolutionary characteristic. This sliding action may have allowed Herrerasaurus to rake its teeth through prey as well as possibly to more easily hold on to small prey as it struggled in between its jaws.

Speed and agility seem to have been key to the hunting strategy of Herrerasaurus which probably would have been seen exhibiting such behaviour as moving amongst the undergrowth and quickly snatching up animals that were scared out of hiding. The immediate clues to this are the legs which have a proportionately short femur (upper leg bone) while the lower leg bones are very long. Additionally Herrerasaurus had a digitigrade stance which meant that it walked on its toes so that the metatarsal foot bones actually served to extend the length of the leg, increasing the stride which in turn increased the top speed of Herrerasaurus. The feet also show a development towards a three toed foot as while the first and fifth digits are still present only one had a (reduced) claw, something which indicates that they were not used to gain extra traction on the ground. In later dinosaurs these toes would become reduced to the point that they were vestigial (present but no longer serving any purpose). Also the pubis on Herrerasaurus points backwards, something that is seen in dromaeosaurid dinosaurs like Deinonychus as well as birds, and further suggests reliance upon agility. The arms are also quite long and may have been used for holding onto prey.

A similar dinosaur to Herrerasaurus that is also from the same location is Sanjuansaurus.

Further Reading

– La presencia de dinosaurios saurisquios en los “Estratos de Ischigualasto” (Mesotriasico Superior) de las provincias de San Juan y La Rioja (Rep�blica Argentina) [The presence of saurischian dinosaurs in the “Ischigualasto beds” (upper Middle Triassic) of San Juan and La Rioja Provinces (Argentine Republic)] – Ameghiniana 3(1):3-20 – O. A. Reig – 1963. – The tibia and tarsus in Herrerasauridae (Dinosauria, incertae sedis) and the evolution and origin of the dinosaurian tarsus – Journal of Paleontology 63: 677–690 – F. E. Novas – 1989. – The complete skull and skeleton of an early dinosaur – Science 258 (5085): 1137–1140 – P. C. Sereno – F. E. Novas – 1992. – Phylogenetic relationships of the basal dinosaurs, the Herrerasauridae – Palaeontology 35: 51–62 – F. E. Novas – 1992. – The skull and neck of the basal theropod Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13 (4): 451–476 – P. C. Sereno – F. E. Novas – 1993. – The pectoral girdle and forelimb of the basal theropod Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13 (4): 425–450. – P. C. Sereno – 1993. – New information on the systematics and postcranial skeleton of Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis (Theropoda: Herrerasauridae) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Upper Triassic) of Argentina – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13 (4): 400–423. – F. E. Novas – 1994.- A new herrerasaurid (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of northwestern Argentina. – ZooKeys (63): 55–81. – Oscar A. Alcober & Ricardo N. Martinez – 2010.