In Depth

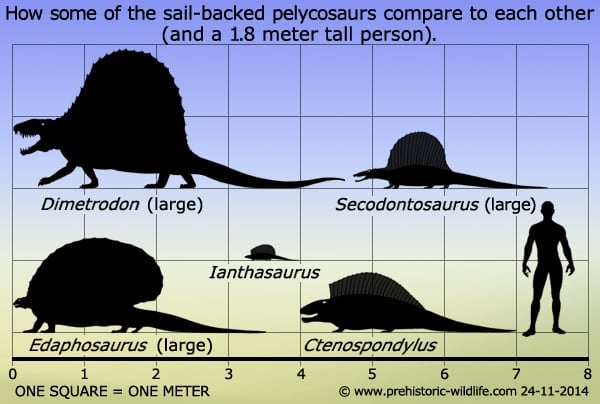

Edaphosaurus is easily one of the more recognisable pelycosaurs, even if the genus is often presented in the shadow cast by the much more famous Dimetrodon. These two genera of pelycosaur are at opposite ends of the ecosystem however, with Edaphosaurus being a plant eater specialising in low growing vegetation, and Dimetrodon being ‘the’ big predator of the time. In fact it is quite probable that Edaphosaurus formed one of the main prey choices for Dimetrodon given that these two pelycosaurs share a near identical geographical and temporal distribution in the fossil record. Both Edaphosaurus and Dimetrodon also seem to have been particularly numerous in the state of Texas, though both are also known from other locations.

The name Edaphosaurus is usually listed as meaning ‘ground lizard’, however, an alternative translation is ‘pavement lizard’, and this is a reference to the arrangement of teeth inside the mouth. These are essentially batteries of small peg-like teeth that would have ground plant matter to a pulp before swallowing. Earlier interpretations of these tooth batteries were actually of the idea that they ground molluscs like shellfish, but later analysis of wear patterns on the teeth have confirmed that plants were the most likely choice for Edaphosaurus. The teeth at the outer rim of the mouth were serrated, greatly helping to shear off fronds of plants.

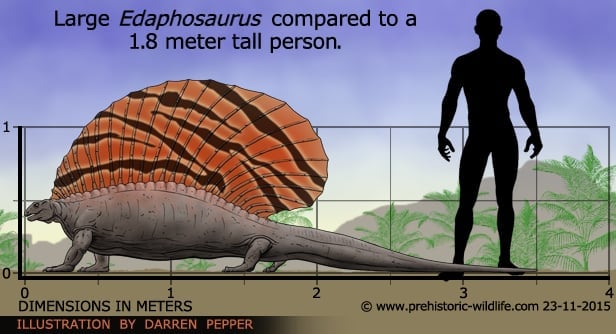

The skull of Edaphosaurus is surprisingly small when compared to the size of the body, but it should be remembered that with a diet of browsing upon plants, a large skull would be simply unnecessary. The lower jaw of Edaphosaurus is very robust and would have helped as an attachment for saw closing muscles to process plant matter. The fact that Edaphosaurus would develop such a strong jaw might suggest that Edaphosaurus were eating tougher, more fibrous plants. It is near impossible to talk about Edaphosaurus without mentioning the sail that grew in the back. This sail was basically a growth of thin tissue, perhaps only skin thin, supported by elongated neural spines. The purpose of this sail still continues to be a source of debate for palaeontologists well over one hundred years after it was first described. Many early ideas about the sail have now been discredited, especially one of the fun ones about how it was a wind sail that would blow Edaphosaurus across a body of water. Another idea about how the enlarged neural spines were anchor points for larger back muscles is now also not widely accepted as there is no conceivable purpose for them.

Two theories that could go either way are predator protection and a fatty hump to survive times of famine. The sail spines in themselves are not terribly strong and offer no protection for areas such as the head or neck. If anything the spines would have given a predator something to bite onto, but perhaps this was the point. Predatory pelycosaurs such as Ophiacodon and Dimetrodon are noted for having very large and powerful heads, and if a predator got confused by the sail pattern of an Edaphosaurus and bit into that, it may have ended up with a mouthful of sail allowing an Edaphosaurus to escape. As far as fat storage is concerned, it is not impossible that the sail could have served this purpose, but it seems to be quite lightly built for this function.

The most tantalizing theory regarding the function of the sail of Edaphosaurus is thermoregulation that in lay terms means control of body temperature. The idea is that when an Edaphosaurus wanted to warm up it would align itself side facing the sun so that blood could be quickly warmed up, and when temperature was right, an Edaphosaurus could turn so that only the thin edge faced the sun. In addition, if an Edaphosaurus got hot it could flush blood into the sail to be quickly cooled. Edaphosaurus are also noted for having small spiny projections that jut out from the sides of the main spines, and these are speculated by some to increase wind turbulence, meaning a much greater cooling effect. The idea of thermoregulation is not accepted by all however, and at least one study focused on the neural spines has cast doubt on this theory.

Perhaps the most likely theory for the sail is that it was there for display. This includes Edaphosaurus being able to recognise other individual Edaphosaurus from other genera sail-backed pelycosaurs (i.e. Dimetrodon), different species of their own genus (each species having its own pattern/colour set), and even signalling to attract a mate. It is also possible that the colour of the sail may have grown more intense at certain times of the year (such as the approach of the breeding season), or even been made more vivid by an individual increasing its heart rate to flush more blood into the sail. In this respect the longer a displaying Edaphosaurus could maintain the colour flush, the fitter it was, and the more worthy it would be to a mate to pass on its genes.

Ultimately the precise function of the sail is still an open debate, but it is also worth noting that the sail may have performed double or even triple duty, fulfilling more than just one purpose. Another fact to remember is that the colour and patterning of the sail of Edaphosaurus is still only speculation, and that reconstructions you see (including the one above) or really just the idea of the artist.

Edaphosaurus is now the type genus of the Edaphosauridae, a group of pelycosaurs that are closer to Edaphosaurus in form. It is generally accepted that Edaphosaurus evolved from smaller insect hunting pelycosaurs like Ianthasaurus that began to appear at least as far back as the Carboniferous.

Further Reading

– Third contribution to the history of the Vertebrata of the Permian formation of Texas. – Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 20:447-461. – Edward Drinker Cope – 1882. – A Description of Edaphosaurus Cope. – Permo-Carboniferous vertebrates from New Mexico. Carnegie Institution of Washington Geological Society of America Special Paper 181: 71–81. – S. W. Williston & E. C. Case – 1913. – Edaphosaurus (Reptilia, Pelycosauria) from the Lower Permian of Northeastern United States, with description of a new species. – Annals of the Carnegie Museum 48 (11): 185–202. – D. S. Berman – 1979. – Aerodynamics and thermoregulatory function of the dorsal sail of Edaphosaurus. – Paleobiology 22: 496–506. – S. C. Bennet – 1996. – Comparative osteohistology of hyperelongate neural spines in the Edaphosauridae (Amniota: Synapsida). – Palaeontology 54: 573–590. – A. K. Huttenlocker, D. Mazierski & R. R. Reisz – 2011.