Sharks frequently appear as the subjects of horror stories which often depict them as cold merciless killers that live to kill. The truth of the matter is not so clear cut as worldwide sharks fill an important part in marine ecosystems that would be irreversibly changed if they disappeared. Today’s sharks however come from a long line of forms that range from the truly unique to downright bizarre.

10 - Elegestolepis

Of all the sharks on this list Elegestolepis is probably the one that will draw the most blanks, mostly because it is only known from placoid scales. In themselves placoid scales are hydro dynamically shaped for decreased water resistance and are a characteristic of all sharks.

What makes the placoid scales of Elegestolepis really stand out though is the fact that they date all the way back to the late Silurian four hundred and twenty million years ago. However Elegestolepis still may not be the oldest shark as other placoid scales seem to date back four hundred and fifty million years ago.

These scales are evidence of the truly ancient heritage of sharks that as a group predates even life on land.

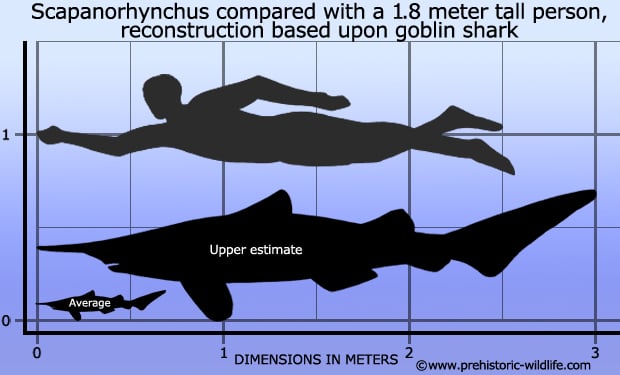

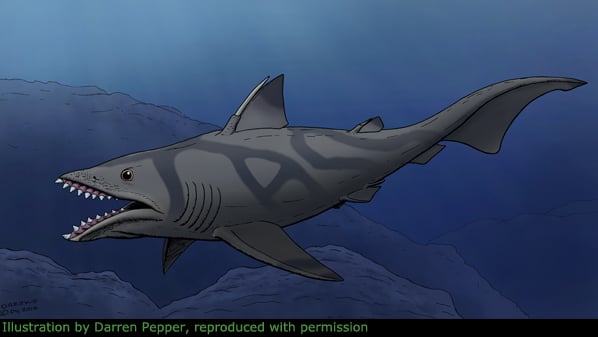

9 - Scapanorhynchus

Scapanorhynchus is thought to be very much like the modern day goblin shark that usually lives in very deep water where sunlight cannot penetrate to light the way. Like the goblin shark, the incredibly long snout of Scapanorhynchus is thought to have been filled with an extensive array of electro receptive ampullae, special sensory organs that detect the electric fields of fish which are generated as they move their muscles to swim through the water.

The sheer number of additional ampullae that could be housed on such a large snout means that Scapanorhynchus could easily make precision strikes on nearby fish even though it would not be able to actually see them.

8 - Cretoxyrhina

Cretoxyrhina had teeth that had a greater than usual covering of enamel, something that would have made them extremely resilient to wear, hence the nickname of ‘ginsu shark’ after the knives. Because these teeth were so hard wearing they are thought to have been able to just as easily cut through bones and shells as they could flesh.

Cretoxyrhina lived during the Cretaceous, a time that saw the oceans dominated by large marine reptiles such as mosasaurs. However with a size estimated to have been up to seven metres long (bigger even than the largest recorded great white shark) Cretoxyrhina was no roll over, and there are even fossils of mosasaurs that have been found with teeth of Cretoxyrhina embedded within them.

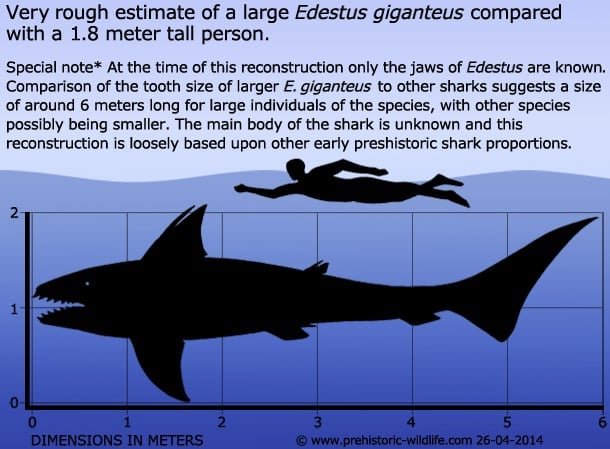

7 - Edestus

Also known as the ‘scissor toothed shark’, Edestus is another example of the bizarre shark forms that seem to have been at their most numerous during the Carboniferous period. However at this time Edestus is classed as a member of the Eugeneodontida a group of cartilaginous fish that is usually placed within the Holocephalii closer to chimaeras than actual sharks. However we still consider it to be shark-like enough to be included on this list.

Edestus was different because as it grew new teeth and gum, the older tissue would not be lost but pushed forward, something that resulted in teeth that faced forward as they were pushed out of the mouth. How Edestus used these teeth to kill and eat prey remains a mystery to be certain, but it likely had a specialised predatory behaviour and prey preference.

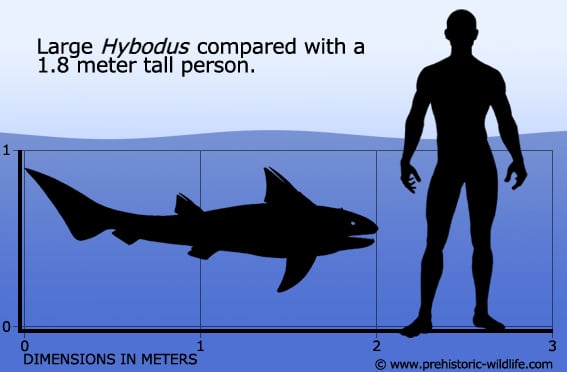

6 - Hybodus

Compared to some other sharks on this list Hybodus was actually quite normal looking, if you discount the large spines that rose up in front of both dorsal fins. Hybodus is one of the few sharks where impressions of its body are actually known, something that has helped palaeoichthyologists to realise this shark had two kinds of teeth. The teeth at the front of the mouth where sharp and pointed like most people imagine shark teeth to be.

The teeth at the rear of the mouth were rounded and robust, useful for crushing the shells of armoured prey. Together these two types of teeth made Hybodus an exceptionally well balanced generalist predator of a variety of different marine animals. Testament to this success is the fact that Hybodus remains have been found all over the world and have a temporal range in the fossil record that lasts from the end of the Permian to the start of the Cretaceous.

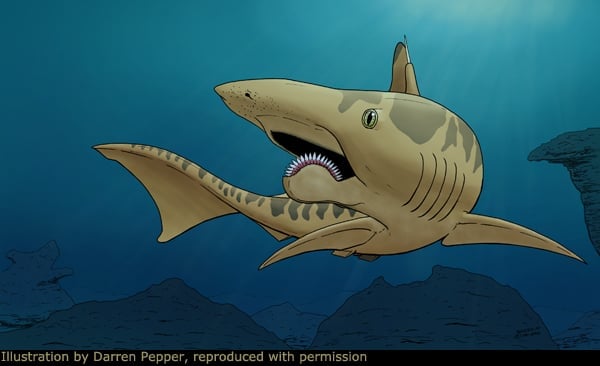

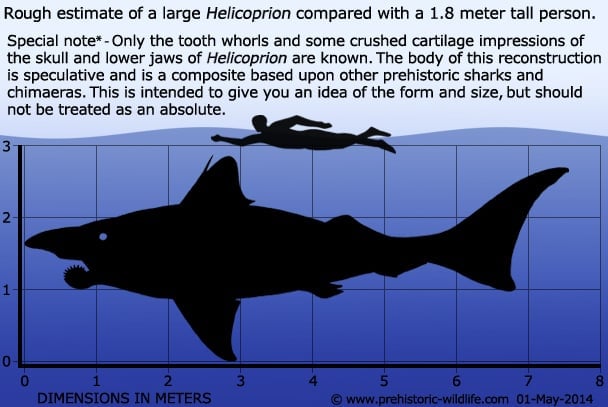

5 - Helicoprion

Like with the previously mentioned Edestus, Helicoprion is another member of the Eugeneodontida. Initially fossils of this shark where thought to be a new kind of ammonite because the teeth were always arranged in a helical spiral.

Later study revealed these ‘shells’ to actually be shark teeth, but here is where the mystery begins. Referred to as a ‘whorl’ these fossils were always found in the same spiral arrangement, and the realisation occurred that this was actually how the teeth were arranged in the living animal. For a long time only these tooth whorls were known, but in 2013 the first description of partial cartilage remains of the skull and jaw were published.

This was the best ever indication for the head shape of Helicoprion, which placed the tooth whorl within a short lower jaw. Testament to the toughness of Helicoprion is the fact that fossils of the genus are known from the late Permian and the early Triassic. This proves that Helicoprion survived the Permian extinction, the largest extinction event in the history of the planet where approximately 95% of all animal species were wiped out.

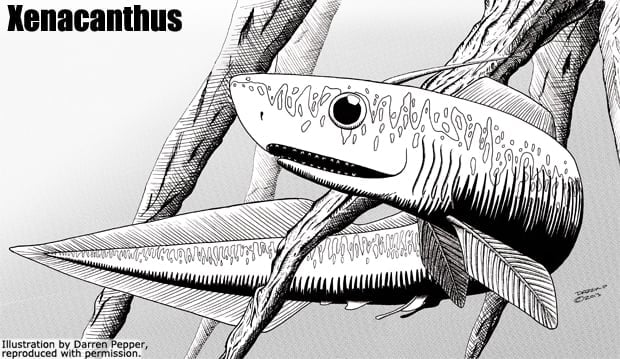

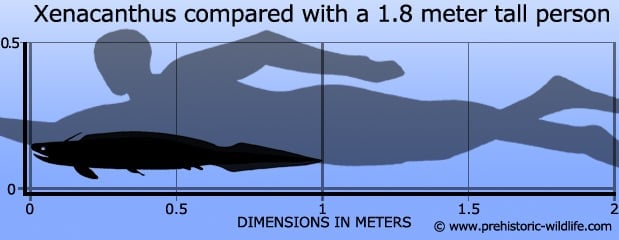

4 - Xenacanthus

With a long slender body Xenacanthus looks like some kind of cross between a shark and an eel. There is no strongly pronounced triangular dorsal fin like other sharks but a single longer fin that runs down the length of the body and around the tail where it continues underneath. A single large spine also rises up from the back of the head, something that in other sharks seems to have been a support for the dorsal fin.

The body of Xenacanthus seems to be ill suited for ocean life, something that has been confirmed by in depth analysis of deposits where Xenacanthus is known from which indicate that it actually lived in freshwater.

From this a picture can be drawn up of Xenacanthus and similar sharks such as Orthacanthus and Triodus living in swamps and waterways that were choked with submerged debris. In these systems an eel like body would allow these sharks to squirm around obstacles without overly large fins like in more classic shark body plans getting snagged upon them.

The eel like form of Xenacanthus also meant that this shark could either lurk amongst debris waiting for prey such as other fish or larval stage amphibians to pass or actually follow them into their hiding places. At the time of the Carboniferous however Xenacanthus would have had to share its water with large temnospondyl amphibian predators, and while fossil evidence shows that at least some xenacanthid sharks ate their young, larger temnospondylids may have eaten the sharks. The spike on the back of these sharks’ heads is thought to have been there for protection from predators like these.

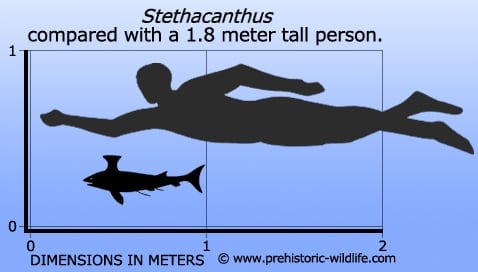

3 – Stethacanthus

Stethacanthus had more of a classic shark shape than Xenacanthus, but it still sported two odd characteristics that make it unique. Most sharks have triangular dorsal fins but the dorsal fin of Stethacanthus was shaped like an anvil with a broad flattened top. On top of this dorsal fin was a growth of enlarged denticles, larger versions of more typical shark scales that gave a jagged toothed appearance to the top of the fin.

These enlarged denticles were also concentrated in a second area on top of the head. There are many theories that try and explain the presence of these areas, but not everyone can agree as to what the true function of these features might have been.

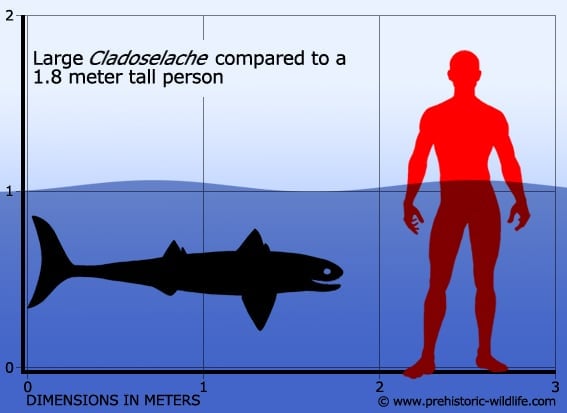

2 - Cladoselache

This is the shark that has arguably made the greatest contribution to shark palaeoicthyology (like palaeontology but with a focus on fish). Cladoselache is known from several exceptionally well preserved specimens that not only show the outer body but even some internal organs as well as the remains of what this shark ate.

These fossils have since helped answer a lot of questions as to how similar ancient sharks are to their modern forebears, and while there are key differences, the overall workings remain very similar. At the time of Cladoselache however sharks were not the dominant predators of the world’s oceans, that title belonged to the arthrodire placoderms such as Dunkleosteus.

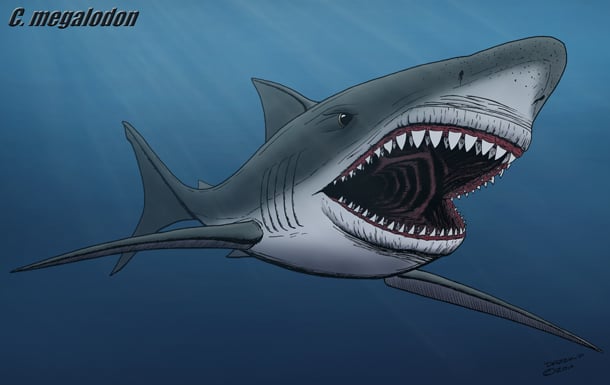

1 - Megalodon

The last shark on this list is the one that most people will be familiar with because of its commonplace depiction in pop fiction such as novels and films. This is O. megalodon, usually just called ‘Megalodon, and it is currently the largest shark thought to ever swim the world’s oceans.

Because megalodon is an oversized shark it is thought that it had a preference for oversized prey such as whales which were far more numerous at the time megalodon was alive. However, megalodon did not kill and eat dinosaurs as it is often claimed in fictional films and books about it for one simple reason; megalodon did not appear until well over thirty-five million years after the dinosaurs went extinct.

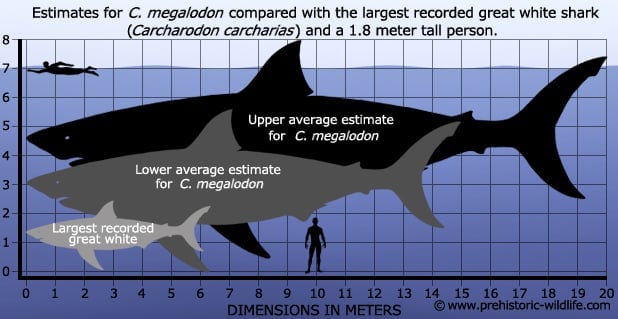

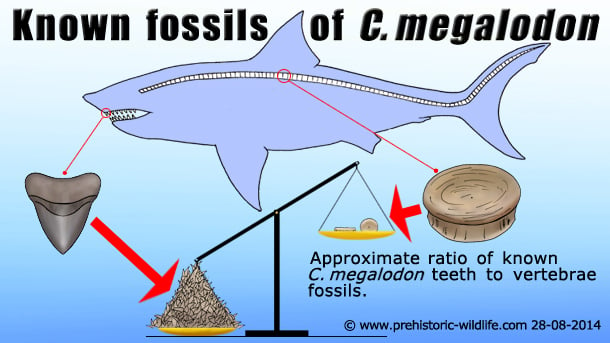

Estimating the size of megalodon has been problematic because apart from a few vertebrae it is mostly only known from teeth. Upper size estimates have placed megalodon at over twenty metres long, but even more conservative estimates place it at being well over double the size of the largest officially measured great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). On a related matter an even greater subject of controversy associated with megalodon is how much it is actually like the great white shark.

Update – There is now a top ten list dedicated entirely to megalodon. CLICK HERE to see it!