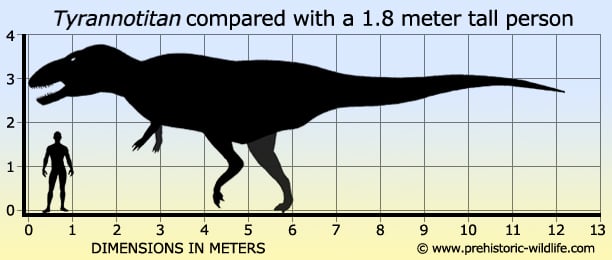

In Depth about Tyrannotitan

With a name like Tyrannotitan you could be forgiven for thinking that this huge theropod was a tyrannosaurid, but in fact it was a carcharodontosaurid Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus, both also from South America.

Tyrannotitan seems to differ from other discovered carcharodontosaurids in that it has proportionately tiny forearms, something that is similar to the tyrannosaurids.

Palaeontologists are confident that Tyrannotitan does not represent a tyrannosaurid because the geographical isolation of South America (it was not yet connected to North America and was long separated from Africa during this time) meant that the tyrannosaurids had no way of reaching the continent.

The species name T. chubutensis is in reference to Chubut Province where Tyrannotitan’s fossils were found.

One key area of difference between Tyrannotitan and the other currently known carcharodontosaurids is the lack of pneumaticity in the sacral (hip) and caudal (tail) vertebrae.

This essentially means that there are no air pockets that could have reduced weight resulting in a solid but heavier skeleton.

Interestingly connected to this observation is the fact that a caudal vertebra of Tyrannotitan has a neural spine (the projection top of the vertebra) twice the height of the centrum, the main body of the vertebral bone that articulates with the other vertebra.

The dorsal (back) and cervical (neck) vertebra do not display neural spines this high, and with this in mind the tail vertebrae may have had them to support a stronger muscle network that was required to carry the tail high and off the ground in the absence of weight saving features such as pneumaticity.

Tyrannotitan teeth do not seem to be as well developed as those of others of its group such as those seen in Carcharadontosaurus.

Tyrannotitan teeth lack the clear curves that facilitate slicing however the general shape makes them part way similar to the teeth of allosaurids like Allosaurus itself.

Given that the carcharodontosaurid theropods are thought to be descended from allosaurid theropods, the teeth of Tyrannotitan may represent a transitional form of the teeth from one changing into another.

The teeth of Tyrannotitan also have denitcles which themselves are dived into two by the presence of a groove.

Denticles are essentially like teeth themselves and may have formed an additional cutting surface increasing the tooth’s ability to pierce flesh.

These tooth denticles may represent an evolutionary experiment that did not carry forward into later descendants that had the flat curved teeth with serrated edges.

As for feeding from a kill, Tyrannotitan probably would have been better at stripping the flesh from a carcass rather than crunching the bones.

Some researchers have asked the question could Tyrannotitan actually be the same as one of the other South American carcharodontosaurids.

This question is based upon sexual dimorphism and on-going evolution of the group and comes about because the small number of specimens combined with their incomplete nature makes it difficult to be immediately certain.

For now Tyrannotitan remains its own genus and will stay so unless fossils and further understanding of the group can prove otherwise.

Should it ever be found the same as another earlier discovered dinosaur then Tyrannotitan will become a synonym to that genus.

Under international rules governing the naming of animals this means that the name Tyrannotitan could not be used for any other discoveries because it is already down in scientific literature as relating to this animal.

Further reading

- – A large Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia, Argentina, and the evolution of carcharodontosaurids – Naturwissenschaften 92:226-230 – F. E. Novas, S. de Valais, P. A. Vickers-Rich & T. H. Rich – 2005.

- – Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tyrannotitan chubutensis Novas, de Valais, Vickers-Rich and Rich, 2005 (Theropoda: Carcharodontosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. – Historical Biology. 27: 1–32. – Juan Ignacio Canale, Fernando Emilio Novas & Diego Pol – 2015.