The Discovery and Naming of Tylosaurus

The discovery of Tylosaurus harks back to the ‘bone wars’, a fierce rivalry between the palaeontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh that took place towards the end of the nineteenth century.

As such the naming history of Tylosaurus is muddled and can cause confusion to those who are not aware of the full history of Tylosaurus’s naming.

The first specimen of a skull and vertebrae discovered in Kansas in 1868 was given the name Macrosaurus prioger by Cope. Approximately a year later Cope re-assigned the material to Liodon. Marsh described a more complete individual in 1872, however his name Rhinosaurus (Nose lizard) had already been used, and its replacement Rhamposaurus (Beak lizard) was also already in use by another animal.

Both of these proposed names referenced the strong snout and this is loosely reflected in the final name of Tylosaurus (Knob lizard). This included all of his specimens as well as the material named by cope to produce the type species T. prioger.

There are a large number of fossils associated with Tylosaurus, mostly from the central United States which was once the sea floor of the Western interior Seaway, but also in other areas of North America.

This has resulted in a great number of species being erected for the genus, although as often proves the case with prehistoric animals whose discovery dates back to the nineteenth century, many of these have been found to be synonymous with existing older species as well as other mosasaur genera.

This is why modern listings of Tylosaurus usually have much smaller species listings than older ones.

One often mentioned species of Tylosaurus, T. haumuriensis described from material in New Zealand has since been declared to be a synonym of the genus Taniwhasaurus type species T. oweni.

Tylosaurus as a Mosasaur

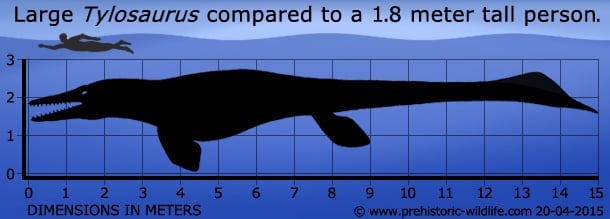

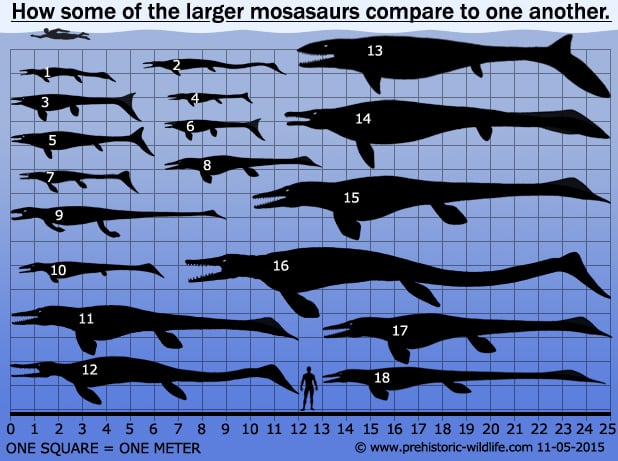

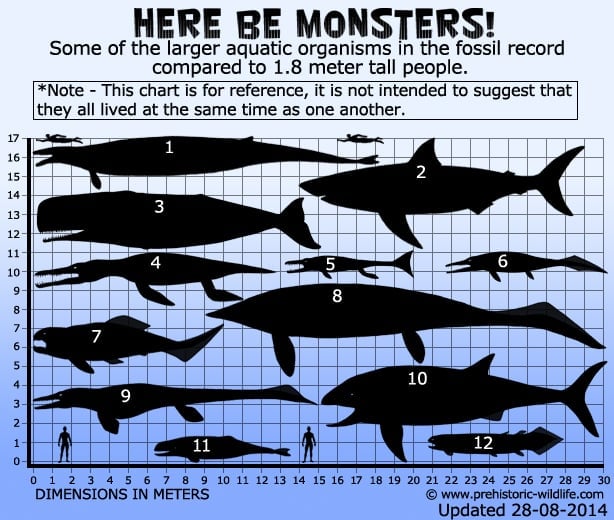

Tylosaurus was one of the larger mosasaurs that lived towards the end of the Cretaceous period, something which has secured its frequent inclusion in popular media such as books and television documentaries. Rivals to Tylosaurus in terms of upper size include Mosasaurus and Hainosaurus.

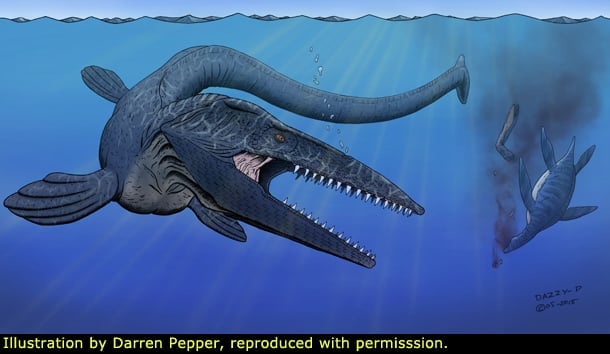

Unlike the earlier pliosaurs which relied upon their flippers for locomotion, mosasaurs relied upon their tails to propel themselves though the water, and Tylosaurus was certainly no exception.

The tail consisted of more that eighty vertebrae, each with a tall neural spine that projected upwards and a deep ’V’ shaped chevron on the underside. These vertebrae resulted in a tail that was laterally compressed but deep so that the maximum surface area available could be used for pushing against the water and propelling Tylosaurus forward.

Although not entirely fusiform like a fish, the overall body shape was adapted to be as hydrodynamic as possible.

When viewed from the side Tylosaurus was a very big animal, but when viewed from the front Tylosaurus would have presented a very small cross-section.

This, combined with the long sloping skull, resulted in a large reduction in the amount of resistance that Tylosaurus experienced as it swam through the water. Also the flippers that were proportionately smaller than those found in pliosaurs were used more for steering than actual swimming, again resulting in a reduction of drag.

The specialised and occasionally damaged snout of Tylosaurus has been suggested to being a weapon used by Tylosaurus against others of its kind during territorial combat. While only speculation, no ecosystem is capable of supporting a high number of large predators in the same area indefinitely, and it is at least possible that Tylosaurus may have been territorial and fought for the right to be active in an area where food was plentiful.

For a long time Tylosaurus was often reconstructed with a dorsal crest which was based upon fossils that appeared to show one running down the length of the animal. Later study revealed this to have been cartilage from the trachea, basically the windpipe that air passes down from the nostrils to the lungs.

In life the cartilage would have kept the shape of the trachea preventing it from closing off when food was being swallowed just like in other animals.

While it is rare for cartilage to be preserved, many sharks which have cartilaginous skeletons have been preserved on many occasions proving that when conditions are right it is possible for cartilage to be preserved, although with varying degrees of success. This is why accurate reconstructions omit the dorsal crest.

Study of another mosasaur named Platecarpus has revealed that at least some mosasaurs may have had a tail fluke similar to the caudal (tail) fin of a shark. For a time Platecarpus was considered to be a one off, but a later discovery of a Prognathodon, a mosasaur genus once thought to have had a straight tail, confirmed that this genus also had a lobed tail fluke.

This started a serious rethink into how mosasaurs were reconstructed, and now the consensus is that in the absence of evidence to the contrary, all mosasaurs, even Tylosaurus, probably had lobed tails.

Tylosaurus - The Apex Predator of the Late Cretaceous Seas

Whereas Tyrannosaurus is dubbed ‘the’ land predator of the late Cretaceous, Tylosaurus would have equally been ‘the’ predator of the late Cretaceous seas, specifically the Western Interior Seaway that once submerged the central portion of the United States and Canada.

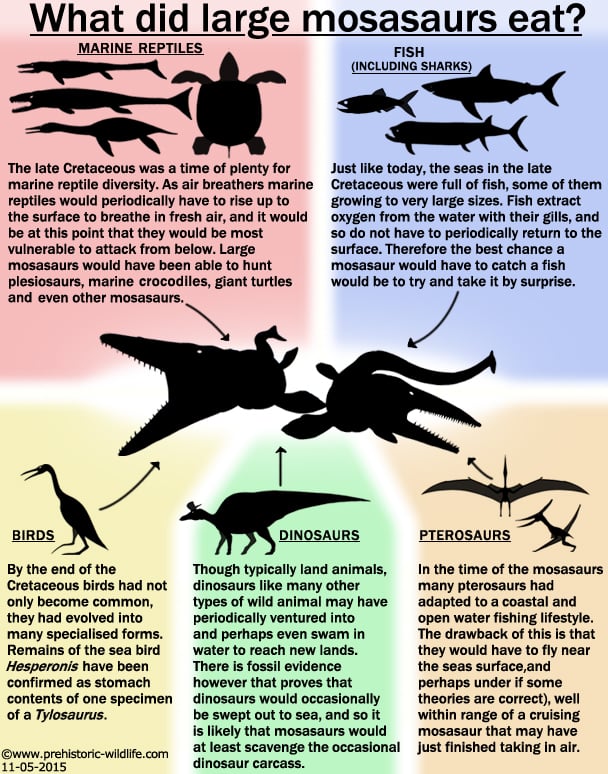

The large size of Tylosaurus meant that it easily attained apex predator status and as such absolutely nothing was off the menu. Fossil evidence exists to support this as stomach contents for Tylosaurus are well known and include fish, sharks, flightless birds like Hesperornis, large marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs and even other mosasaurs

There is also evidence to suggest that Tylosaurus fed upon dinosaurs, as evidenced by a specimen dubbed the ‘Talkeetna Mountains Hadrosaur’ from the Matanuska Formation in Alaska. The bones associated with this hadrosaur have puncture marks that are very similar to the tooth size and arrangement, in fact detailed study has shown that a feeding Tylosaurus is the most likely cause of the marks.

However this case of a Tylosaurus feeding upon a dinosaur is most likely a case of scavenging, with a Tylosaurus discovering the body of a dinosaur that had drowned and been swept out to sea. When animals die, gases given off by the decomposition processes build up inside the body causing it bloat and float up to the surface.

Had a mosasaur fed from the carcass before this, the gashes and puncture wounds from the teeth would have caused the gases to escape causing the dinosaur to sink straight to the bottom rather than being washed out with the tides and currents.

The carcass then seems to have sunk to the bottom through the release of the gas, either through natural decomposition, or more likely scavenging of other ocean predators such as sharks like Squalicorax or perhaps even the Tylosaurus itself.

Study of the sea floor where the hadrosaur skeleton was found also shows that the largest concentration of flesh was on the side which was in contact with the ground. This shows that while the Tylosaurus was feeding from the carcass it was unable to reach the bottom side.

If the Tylosaurus had attacked a living hadrosaur you would expect to see signs of flesh removal and tooth marks all over. The greatest number of tooth marks are on the outer extremities of the hadrosaur such as the lower legs which a mosasaur would have had an easier time manipulating rather than the bulk of the main body.

Also the amount of flesh on the bone of the lower legs would have been much less, resulting in a higher incidence of bite marks as the teeth bit through the thin muscle and straight into the bone.

Although Tylosaurus had large teeth and powerful jaws, these may not have been the primary weapons of attack, at least not in the expected sense. The most forward areas of the jaws have a severe reduction in teeth to the point of being toothless.

The snout is also reinforced making it stronger than other marine reptiles. Additionally some Tylosaurus snouts show signs of compression damage that seem to have been caused by a violent impact.

These all point to Tylosaurus relying upon brute force to ram prey at high speeds. Such an attack probably would not kill prey outright, but could quite easily stun it so that it floated hopelessly in the water.

It would have been particularly effective against other marine reptiles as they approached the surface to breathe air. Stunning them by ramming would not only make them a sitting target, but without a fresh supply of air they could have possibly drowned if Tylosaurus did not immediately return to finish its prey off.

Despite the devastating nature of such an impact, such as attack would actually require patience and timing to execute properly, as while the prey was smaller, it was almost certainly more manoeuvrable than a fully grown Tylosaurus.

This makes attacks in the same depth plane unlikely because despite its speed, prey would have likely seen the attack coming and taken avoiding action.

This is why it makes the most sense for a marine predator to approach its target from below as not only can it home in unseen, other sensory adaptations such as the pressure and electro receptors of fish tend to work in sideways directions, and any scent from the predator would also drift sideways in the ocean currents, not up.

This style of attack has also been implied for the giant shark C. megalodon as well as predatory whales such as Livyatan, and suggests that while the predators and prey were different throughout the ages, the actual method of attack was principally the same.

Smaller prey items like flightless birds such as Hesperornis and sea turtles probably did not require such special hunting strategies and may be cases of opportunistic feeding.

The one drawback of being the biggest predator in the area is that you have to take every opportunity you can to feed, or you risk starvation. Cases of Tylosaurus killing sharks and other mosasaurs could be presented as a case of intraguild predation. This is where a predator not only kills for food, but also removes potential competition from the ecosystem in the process.

Further Reading

- – The vertebrate fauna of the Selma Formation of Alabamam: Part VII The Mosasaurs. Fieldiana: Geology Memoirs 3(7):365-380. – D. A. Russel – 1970.

- – Tylosaurus ivoensis: a giant mosasaur from the early Campanian of Sweden. – Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 105: 73 – 93. – J. Lindgren – 2002.

- – New data on cranial measurements and body length of the mosasaur, Tylosaurus nepaeolicus (Squamata; Mosasauridae), from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas.

- – Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 105 (1-2): 33-43. – M. J. Everhart – 2002.

- – Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas.

- – The Mosasaur. 7: 41–46. – M. J. Everhart – 2004. – Earliest record of the genus Tylosaurus (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Fort Hays Limestone (Lower Coniacian) of western Kansas.

- – Transactions 108 (3/4): 149-155. – M. J. Everhart – 2005. – Tylosaurus kansasensis, a new species of tylosaurine (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas, U.S.A.

- – Netherlands Journal of Geosciences-Geologie en Mijnbouw 84 (3): 231-240. – M. J. Everhart – 2005.

- – A bitten skull of Tylosaurus kansasensis (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and a review of mosasaur-on-mosasaur pathology in the fossil record.

- – Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 111 (3/4): 251–262. – M. J. Everhart – 2008.

- – Redescription and rediagnosis of the tylosaurine mosasaur Hainosaurus pembinensis Nicholls, 1988, as Tylosaurus pembinensis (Nicholls, 1988).

- – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 416–426. – T. S. Bullard & M. W. Caldwell – 2010.

- – Occurrence of a tylosaurine mosasaur (Mosasauridae; Russellosaurina) from the Turonian of Chihuahua State, Mexico.

- – Bolet�n de la Sociedad Geol�gica Mexicana. 65 (1): 99–107. – Abelaid Loera Flores – 2013.

- – Tylosaurine mosasaurs (Squamata) from the Late Cretaceous of northern Germany. – Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 55–71. – J.J. Hornung & M. Reich – 2015.

- – Re-characterization of Tylosaurus nepaeolicus (Cope, 1874) and Tylosaurus kansasensis Everhart, 2005: Ontogeny or sympatry?.

- – Cretaceous Research. 65: 68–81. – P. Jim�nez-Huidobro, T. R. Sim�es & M. W. Caldwell – 2016. – Reassessment and reassignment of the early Maastrichtian mosasaur Hainosaurus bernardi Dollo, 1885, to Tylosaurus Marsh, 1872.

- – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. – Paulina Jimenez-huidobro & Michael W. Caldwell – 2016.

- – The Smallest-Known Neonate Individual of Tylosaurus (Mosasauridae, Tylosaurinae) Sheds New Light on the Tylosaurine Rostrum and Heterochrony.

- – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (5): 1–11.

- – Takuya Konishi, Paulina Jim�nez-Huidobro & Michael W. Caldwell – 2018.

- – A new species of tylosaurine mosasaur from the upper Campanian Bearpaw Formation of Saskatchewan, Canada.

- – Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (10): 1–16. – P. Jim�nez-Huidobro, M. W. Caldwell, I. Paparella & T. S. Bullard – 2018.

- – Allometric growth in the skull of Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and its taxonomic implications.

- – Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 66: 75–90. – R. F. Stewart & J. Mallon – 2018.

- – A New Hypothesis of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Tylosaurinae (Squamata: Mosasauroidea). – Frontiers in Earth Science. 7 (47): 47. – Paulina Jim�nez-Huidobro & Michael W. Caldwell – 2019.

- – A new high-latitude Tylosaurus (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from Canada with unique dentition (MS). – University of Alberta. – S. T. Garvey – 2020. – Craniofacial ontogeny in Tylosaurinae. – PeerJ. 8: e10145. – A. R. Zietlow – 2020.