In Depth

Named in honour of the palaeontologist Jim Eyles, the Eyles’ Harrier is an extinct harrier, and one that grew to a particularly large size for the kind of bird of prey that it was.

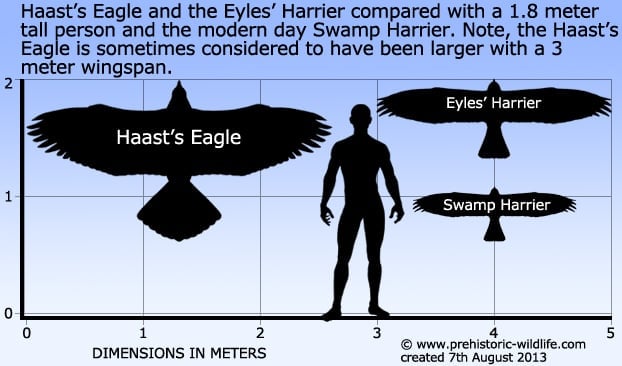

The Eyles’ Harrier is often considered to have been similar to the modern day Swamp Harrier (Circus approximans), though the Eyles’ Harrier is estimated to have been two and half to three times heavier than a large Swamp Harrier with a wingspan a quarter to two thirds as large as a Swamp Harrier.

The remains of Eyles’ Harriers and Swamp Harriers can be both found in New Zealand and from the same times, though an interesting thing of note is that the Swamp Harrier does not seem to have become established and widespread in New Zealand until after the Eyles’ Harrier disappeared.

The Swamp Harrier is also known from nearby locations such as Australia, Fiji, Vanuatu and New Caledonia, so it’s possible that the earliest Swamp Harrier remains on New Zealand may have been from visiting individuals that were either migrating or simply searching out new hunting grounds.

The fact the Swamp Harrier did not begin to become established in New Zealand until the beginning of the decline of the Eyles’ Harrier suggests that the two birds were so similar in ecological niche that the ecosystems of New Zealand could not support both.

The Eyles’ Harriers being larger than the Swamp Harriers, meant that they could drive off their smaller rivals.

Harriers are noted for flying high above open ground and looking for ground dwelling prey such as reptiles, small mammals and birds that lived on the ground.

As such is probable that Eyles’ Harriers hunted in a similar fashion, except they hunted the smaller ground dwelling animals of Pleistocene/Holocene New Zealand.

It is likely that during this time the Eyles’ Harriers were among the apex predators of New Zealand, though the largest bird of prey here that lived at the same time as the Eyles’ Harriers was the Haast’s Eagle, the inspiration for the pouakai bird of Maori legend and a much heavier bird of prey that specialised in hunting the moa birds of New Zealand.

Both the Eyles’ Harrier and the Haast’s Eagle were among the largest birds of prey for their respective types, and both seem to have suffered and gone extinct from the same cause; human habitation.

The first people are believed to have settled New Zealand around 1250-1300AD, and the establishment of permanent settlements led to two things; the clearing of habitats and the hunting of the larger animals on the islands for food.

By about 1400AD, the moa were gone, and the Haast’s Eagle disappeared along with them.

No one knows for certain when the Eyles’ Harriers went extinct, but since they were generalists, they had the chance to survive for a bit longer, but continued pressure from people and perhaps even Swamp Harriers could have driven them into extinction.

With people hunting the larger game, only smaller animals that were harder to catch and offered less food were available to the Eyles’ Harriers.

The Swamp Harriers however were smaller, more nimble and did not need to eat as much food to survive, and could have steadily replaced Eyles’ Harriers as they steadily declined in numbers from lack of suitable prey.

This is analogous to what happened in North America between Dire Wolves (Canis dirus) and Grey Wolves (Canis lupus) at the end of the Pleistocene.

A marked decline in large animals occurred at this time, which may or may not be in part due to the appearance of the first people on this continent, but the point here is that the decline of larger prey had a knock on effect which caused the decline of the large predators.

Similar but smaller predators however, managed to survive into modern times simply because they did not need to eat as much to survive, which is why there are Grey Wolves in North America today, but no longer any Dire Wolves.

It is just possible that Eyles’ Harriers may have managed to survive until the late nineteenth century.

This idea is centred around the claim that when travelling the Landsborough River Valley in the 1870s, explorer Charles Edward Douglas shot and subsequently ate two raptors of notably large size.

Douglas claimed these to have been two pouakai, a legendary bird of Maori legend believed to have had its origin from early encounters between early settlers and Haast’s Eagles.

But Maori people of the time insisted that the pouakai was a bird not seen in living memory, and the disappearance of the moa several hundred years earlier also supports this.

Instead it is more probable that the birds in question may have actually been Eyles’ Harriers since their extinction seems to have been slower and not so directly tied with one event.

The Eyles’ Harrier can be taken as an example of insular gigantism, however, at the other end of the scale there is another prehistoric harrier that lived in the Pacific which serves as an example of insular dwarfism. This is the Wood Harrier.

Further Reading

- - New Zealand’s pre-human avifauna and its vulnerability - Richard N. Holdaway - 1989.

- - A reappraisal of the late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of Pyramid Valley Swamp, North Canterbury, New Zealand - Richard N. Holdaway & Trevor H. Worthy - 1997.